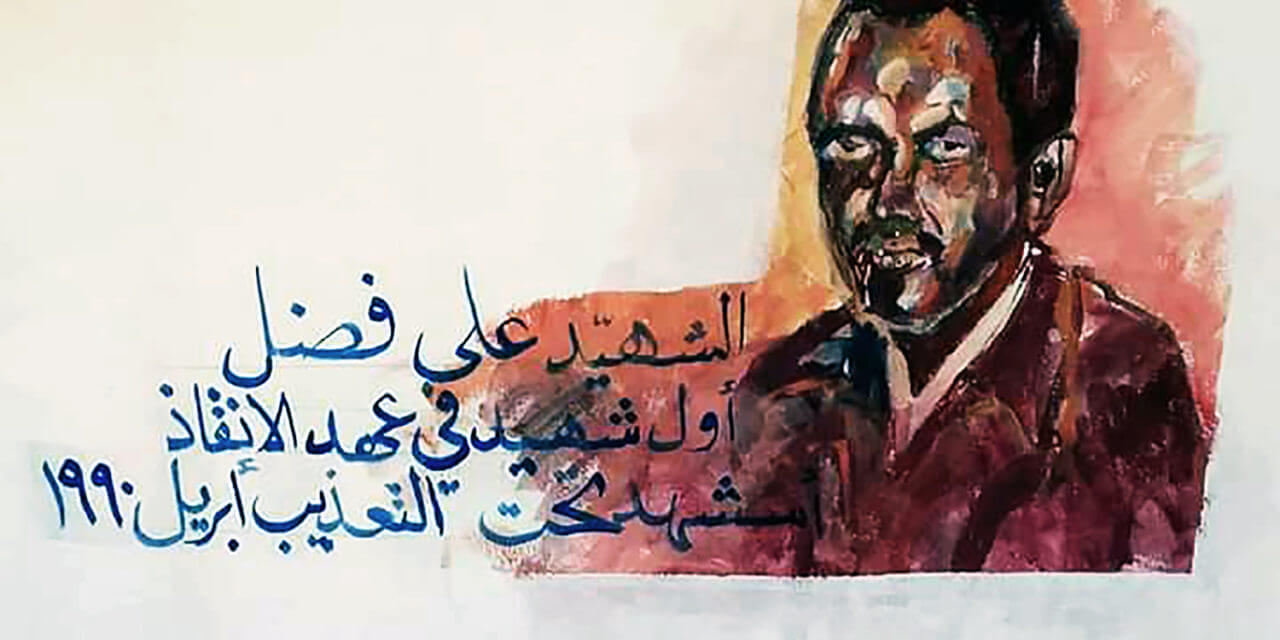

A mural of Dr Ali Fadul, a Sudanese doctor and member of the Sudan Doctors Union who was detained, tortured and finally killed on April 21, 1990. (cc) AlAdwaa.Online | Alaa Eliass

Along with other professionals, doctors played a central role during Sudan’s uprising. Behind the scenes, doctors helped transform what started as protests over bread prices into a revolution.

Nationwide mass protests that started in December 2018 and a military coup have ended the 30-year rule of Omar al-Bashir and fostered a powerful, if still uncertain, pro-democracy movement in Sudan. This was achieved in large part by an alliance of doctors, lawyers, journalists, engineers and teachers organised under the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA).

Doctors have played a particularly prominent role in shaping the protest movement that brought down Bashir – and there is a history. Since Sudan gained its independence in 1956, the country faced several uprisings.

In October 1964, the Sudanese people revolted against General Ibrahim Aboud, the very first revolution against a sitting president in the history of the African continent and the Middle East, where militant coups were the norm.

In April 1985, President Gaafar al-Nimeiry’s government was overthrown in a military coup after more than a week of demonstrations and strikes touched off by increased food prices and growing disaffection with al-Nimeiry. During all three revolutions and other protests, doctors were on the frontlines and paid a high price for their defiance.

The price of defiance

Dr Babiker Abdelhameed Salama became an icon of Sudan’s latest revolution. In the early days of the uprising, on January 17, 2019, Dr Babiker was killed, shot by the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) while he was trying to treat wounded protesters during a peaceful demonstration in Khartoum.

Only in his late twenties, Dr Babiker was providing medical assistance to wounded protesters inside a house in the Burri neighbourhood of Khartoum. Due to the severity of some of the injuries he was treating, he decided to leave the house and approach the members of the NISS with his arms raised, requesting to be allowed to transfer the injured to the nearest hospital. When asked by the officers if he was the doctor treating the protesters, Salama responded affirmatively. Immediately after his response, members of the NISS shot him. He died at the Royal Care International Hospital at 6:30 PM the same day.

Dr Babkir wasn’t the only doctor who was killed under Bashir’s rule. There is a long list of victims. In the wake of the Sudanese Doctors strike in 1990 Dr Ali Fadul, a Sudanese doctor who was a member of the Sudan Doctors Union was detained, tortured and finally killed by NISS on April 21, 1990. His body showed strong evidence of physical abuse and a fatal head injury. However, his death certificate was released, stating malaria as the cause of death, and the case was never investigated.

The list of killed doctors goes on, for example, Dr Salah Mudathir Al Sanhouri (34), killed on September 27, 2013, during peaceful protests against lifting subsidies on fuel; Dr Sara Abdelbagi who was shot and killed outside her uncle’s home in the Aldorashab neighbourhood of Khartoum on September 25, 2013; Mahjoub el-Taj Mahjoub, a second-year student at the Faculty of Medicine of El Razi University, reportedly died “after being subjected to beating and torture” while in police custody in January 2019.

Throughout the 30 years of Bashir’s rule, his regime paralysed professional unions. Sudan’s doctors repeatedly tried to form a unifying body. In 2010 doctors managed to establish Sudan’s Doctors Committee, and they organised a strike demanding a salary raise and more resources for hospitals across the country. In 2016 they organised another strike under the title ‘For you citizen’, again demanding more support for Sudan’s medical sector, laws to protect doctors, better training for health care professionals and the reopening of Khartoum Hospital.

In 2016 the Central Committee of Sudan Doctors (CCSD) was formed but immediately suppressed by the government. The founders were arrested and detained in prison. But this didn’t stop the CCSD. Right after their release from prison, the CCSD founders and their members started to meet again, planning new strikes aimed at improving healthcare across Sudan. In 2019, the CCSD became a vital stakeholder of the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA).

“The situation in hospitals was terrible. We had an enormous shortage of clinical tools and drugs.”

Dr Montasir Bashir

In shambles: Sudan’s healthcare sector

Dr Montasir Bashir, who is a member of the CCSD and one of the doctors who was leading the strikes, says “it was expected that the doctors would lead this revolution for many reasons. The situation in hospitals was terrible. We had an enormous shortage of clinical tools and drugs. We didn’t have beds in the emergency rooms.”

“The situation of the public hospitals was disastrous,” confirms Omnia Hamza, a 24-year-old pharmacist who works at the Public Health Institute, Federal Ministry of Health. “There was massive corruption, a huge shortage of essential and lifesaving drugs, and we saw people dying every day in public hospitals because we couldn’t provide a USD 2 or 3 medicine.”

Besides, says Dr Montasir, “there was a great shortage of staff, and huge pressure from patients and their relatives who thought that this shortage was because doctors neglected their duties or didn’t care enough,” Dr Montasir explains. “It wasn’t true,” the shortage was caused by the authorities and their inadequate healthcare spending, he says. “All the budget was spent on the presidential militia instead.” “To sum it all up – the situation was awful,” says Omnia.

To make the already dire situation worse, the medical directors in charge were directly selected by the government. This not only ensured the government’s agenda was upheld but also protected the regime and its henchmen. When people got killed by the regime’s militias, the medical directors would ensure the reports would cover-up the causes of death.

“We saw people dying every day in public hospitals because we couldn’t provide a USD 2 or 3 medicine.”

Omnia Hamza

The 207 days strike

On July 19, 2019, the CCSD announced the end of a strike, which lasted for 207 days, in protest against killing people who took to the streets. The strike ended after the signing of the agreement between the Sudanese Military Council and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) alliance.

During the strike, the staff of 32 government hospitals and several private hospitals, committed themselves to take care of critical cases injured by accidents and other emergencies, intensive care and dialysis departments, cancer and newborn departments, but did not treat non-critical cases.

Following the killing of Dr Babkir, the strike was widened, and doctors withdrew from military hospitals, accusing the military of not protecting demonstrators. However, to support the injured and wounded protestors, medics provided mobile services, surgeries, drugs and other health services for free.

When paramilitaries moved in to disperse a protest sit-in in front of the Army General Command in the centre of Khartoum on June 3, 2019, and killed 127 people, doctors yet again were present in the frontlines, treating the injured protestors while being under fire. Two doctors died that day, and many were injured.

The 207 days strike is described as the longest doctor’s strike in Sudan’s history, sustained civil disobedience that provoked the former regime, and put medical professionals high on the target list of the old government.

“They have never liked us,” Dr Suleiman explained to the Mail and Guardian. “They blame us for the protests. I stopped carrying my ID and phone to hide my profession to stay safe.”

I stopped carrying my ID and phone to hide my profession to stay safe.”

Dr Suleiman

Was the price too high?

“When you look at the very high price that we had to pay to accomplish our revolution, you will always feel that what we have achieved is not enough, we want more,” says Omnia. “No doubt it’s nothing less than a sweeping change at all levels, but for me, there are still priorities that the government needs to take seriously. I am optimistic that we are all having genuine intentions to rebuild Sudan, and a long way is waiting for us.”

“We have high expectations for the post-revolution Sudan. We are waiting for more from the current government,” says Dr Montasir. “But at the same time we know that the new government inherited a massive burden from the old regime and to fix this whole chaos, it will need a longer time. “I believe that our new Prime Minister, Mr Hamdok is a capable leader,” he adds.

Dr Abdalla Ahmed, a 24-year-old member of the CCSD says: “I am still waiting to see the change that I put my life at risk for! I am waiting to see a tangible change in our daily life. I do not doubt that our revolution government is competent, but I also think that it should speed-up the change process a little.”

“I am saying that because like every other Sudanese, I have seen a lot throughout the revolution. The militias have attacked me while I was doing my job. I have seen many young lives fading-away. The road of this revolution was filled with a lot of blood, and therefore one would expect the maximum results at all levels,” Dr Abdalla adds.

“I am still waiting to see the change that I put my life at risk for!

Dr Abdalla Ahmed

What’s next for Sudan’s health sector?

“After the revolution and the formation of the transitional government, I joined the strategic planning office at Central Committee of Sudan Pharmacists, which I was already part of, but in another function,” says Omnia. She and her colleagues are tasked with planning the overhaul of Sudan’s health and pharmaceutical sectors. “I am representing the committee in the national task force that is working on the national health policy and strategic plan for the transitional period. We have been working on it already for two months.” According to Omnia, the goal is “improving the whole health system”.

Dr Montasir says it is “too early to measure any changes now”, but he is content with the steps taken so far, saying it is high time “to change the whole old, useless healthcare system”. Meanwhile, he focuses on his work again, “following-up with patients who have been injured in the days of the revolution. For me, they are a priority, and their treatment expenses should be paid by the government.”

With their long history of struggle, Sudan’s doctors, amongst many others, have set an impressive example of courage, professionalism and sacrifice for the sake of others. And their struggle isn’t over. It falls on them and other stakeholders of the Sudanese Professionals Association, and the relatively narrow demographic they represent, to unite disparate opposition factions — from left-wing groups to religious parties to armed rebels — around a political agenda that calls for civilian rule, women’s empowerment and an end to the nation’s civil wars.