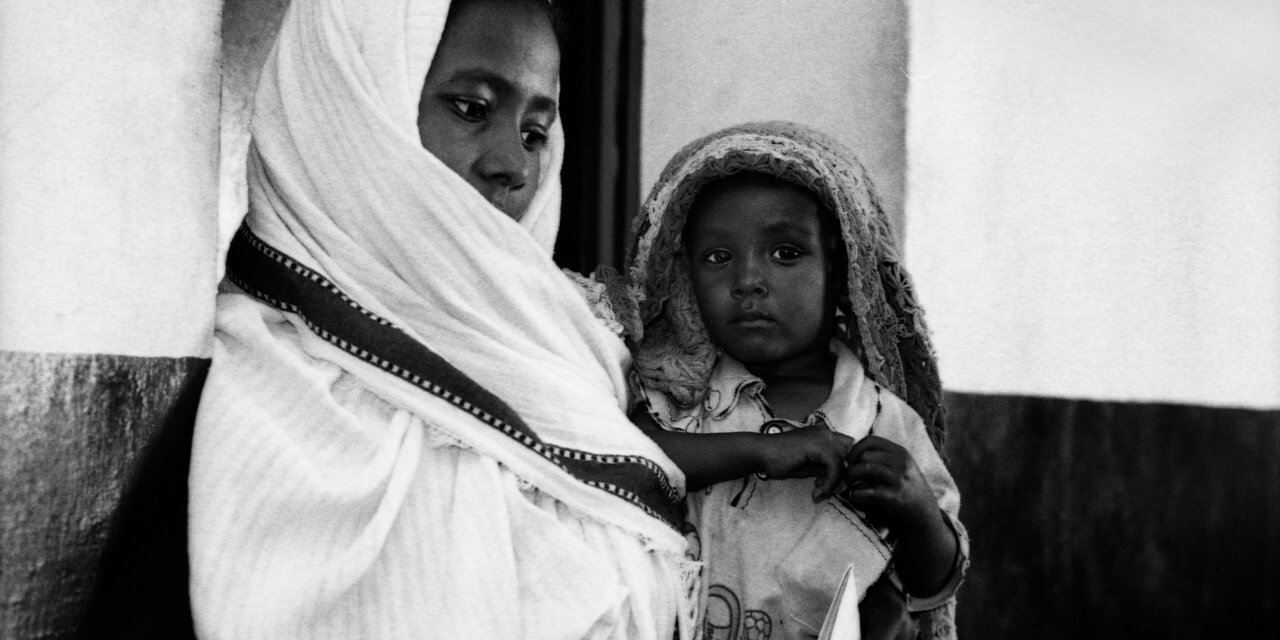

A Sudanese mother and her child. Photo: Frank Keillor | October 1984

Women in Sudan hope for greater freedoms and equality in the post-Bashir era. Elzahraa Jadallah comments that restrictive laws and practices have harmed all women, particularly single mothers and divorced women.

Being born and living in a country like Sudan is one of the hardest and most challenging fates. Right now everything is expensive – the rent, groceries, quality education, reasonable healthcare and other public services. The economic crisis also means that many people are not gainfully employed. Adding a fragile security situation and a myriad of other issues on top of that, it is hard for anyone to live in Sudan under these conditions.

But as a woman, things are even harder. The ousted regime of Sudan’s former president Omar al-Bashir had been in power since a coup d’état in 1989. In April 2019, after months of widespread protests, the rule of the Islamist National Congress Party (NCP) and its leader came to an end. During their 30 years in power, restrictive laws based on Islamic jurisprudence, or Sharia, stifled women’s rights across the country.

Restrictive laws based on Islamic jurisprudence, or Sharia, stifled women’s rights.

Although women played a significant role during the uprising that led to Bashir’s fall, the legacy of the former regime is still an everyday reality for most Sudanese women. Renegotiating and overcoming entrenched societal, legal and economic constraints takes time. So for now, despite some improvements, life for women in Sudan is anything but easy. Now imagine you are a divorced single mother!

I am a divorced, single mother living in Sudan. I am struggling to make ends meet for my two children and me, doing everything I can amidst social stigma, and the discriminating and sexist law system that offers no protection for a single mother and her children.

Personal Status Law

Sudan’s Muslim Personal Status Law does not grant women equal rights. The legislation, regulating women’s rights within marriage, custody, divorce and inheritance, was adopted in 1991, and it is still in place today.

Under the law, a divorced mother is entitled to custody of her male children until they are seven years old and females till they are nine. The court may extend these periods if it is proven to be in the interest of the wards until the sons reach puberty and the daughters get married.

The father or another male guardian is to maintain scrutiny of all matters related to the raising of children in the custody of their mother.

The custody of a woman of a different religion to the father ends when the child is five or earlier if there are fears for their faith being affected. Child support is the responsibility of the father until the daughter is married, and the son is of an age when he can earn his living.

Mothers lose custody of their children if they remarry, have a time-consuming job or study.

Mothers lose custody of their children if they remarry, have a time-consuming job or study. Besides, due to regulations implemented by the NCP regime, women cannot get any legal documents, certificates or IDs for their children issued without the father’s presence or approval and they cannot travel with the children abroad.

Men have been using these laws as a tool to suppress their ex-wives and control their lives. These weak laws and regulations have had devastating effects on children and their mothers.

On the edge of despair

On June 30, 2018, my two children whom I have the full custody of according to their age (five and six at the time), were taken by their father without my consent or even knowledge. I was preparing dinner when he came and picked them while they were playing right outside of our flat’s open door inside the building.

When I stopped hearing their voices, I rushed to the street and saw the car leaving. My attempts to call him remained unanswered. Later a friend of my ex-husband called and told me that “your children are with us. They are where they belong, and you will never see them again.”

After the call, I immediately went to the police station and reported the incident. This marked the beginning of a frustrating four-day-process to get my children back.

The first thing I was told at the police station: “It’s not a crime, and there’s no law forbidding the father from taking his children even if he doesn’t have the custody.” They said, “he will get tired and burdened by them, and return them in no time”.

“There’s no law forbidding the father from taking his children.”

Eventually, the police officers agreed to start the process of issuing a search and arrest warrant under a “Negligent act causing harm” charge. Even though the charge was too benign given the circumstances, this was the only avenue possible.

The following days required multiple visits to the police station, the prosecutor’s office, child services and the personal status court which are meant to help with cases such as this one.

I begged different parties for assistance but had the feeling no one really wanted to help. In Sudan, you can get things done if you know the right people, occupying the right positions. But after going through many intermediaries, even asking people in higher positions, my search for help was futile. I was on my own.

Tethering on the edge of despair, I turned to my online community. I posted pictures of my children, asking anyone who sees them get in touch with me urgently. People would share my post and express their views about my struggles. This, of course, angered the police, who claimed my actions put them in a bad light. However, I was just a mother trying to get her children back.

“I can’t do anything for you now.”

The police concluded that my case was not within their purview and that I should direct my complaint to specialised institutions. I knocked on all the doors I could think of. The personal status court set a timeframe of months before they could handle my case, and child services simply refused to do anything when I approached them on the second day.

The head of the police station received an order to stop handling my case and to refer me to the specialised institutions – which I had already reached out to. He told me “I can’t do anything for you now”. However, he gave me a glimpse of hope: “If you get an address within 24 hours, I will send officers with you to get your children.”

The breakthrough

As fate would have it, this is when the online community came to my rescue. I received information from a woman who said she saw my children. After some back and forth, she trusted I was their mother, and I was able to get an address from her.

The head of the police station kept his word and sent five officers with me to the address in the outskirts of Khartoum. I found my children playing unsupervised on the street. Their clothes were dirty, and they had lost looks in their eyes.

“I was on the street waiting for you. I knew you were coming,” my daughter said. My heart lifted because I knew then that throughout the four days of separation, they never lost hope. They knew I had not abandoned them.

“I was on the street waiting for you. I knew you were coming.”

This was two years ago. My children and I had to change our address, phone number and go to therapy. A case against my ex-husband was filed but went nowhere, as I could simply not afford it, lacked the time to pursue it, and the laws and regulations are still the same.

Unfortunately, the head of the police station who ‘unofficially’ assisted me was relocated to another state. I am grateful for his assistance, and I am so thankful to the woman who cared for my case and provided the crucial lead to get my children back, and for the thousands of people that cared, shared the post and tried to help, when the official entities had failed us.

Sadly, my children and I could go through this all over again, either because my ex-husband finds us and takes my children again, or because he files for custody, as they have, by now, almost reached the age where my custody right can be revoked. Our fate would be in the hands of a judge’s personal view.

I was lucky to get my children back. This is not the case for all mothers in Sudan. As a journalist who writes extensively about women rights, I heard stories that are far more dreadful than mine.

I have a friend who has not seen her children in over ten years. She is still waiting and struggling, as their father fled the country with them. They grew to become men without their mother. Fathers can get passports issued and travel with their children without the mothers’ knowledge and it is illegal for mothers to do the same.

It was hope, determination and the help of other people that brought my children back to me.

Parental kidnapping is not a crime in Sudan. When you add to that all the laws which discriminate against women and mothers, we are facing a bleak horizon, despite the new post-Bashir era in Sudan.

People are meant to enjoy the freedoms they struggled for. I cannot help but wonder where we, as women and mothers stand in the list of priorities of the transitional government.

Given that calls of activists, feminists and women rights advocates still fall mostly on deaf ears, I am not so optimistic, but I remain hopeful and determined. After all, it was hope, determination and the help of other people that brought my children back to me.