People in Sudan’s capital Khartoum donating blood for the victims of the violent incident in el-Geneina. (cc) Ayaa Shamat | January 2020

Sudan is facing critical shortages of blood. The supply of life-saving transfusions is insufficient to keep up with demand. In a collaborative effort, various initiatives in Sudan try to meet needs.

Sudan’s healthcare system suffered from many drawbacks, mainly due to economic and managerial reasons followed by prolonged political instability and sanctions. Healthcare, simply put, wasn’t a priority. Sudanese military and security spending under the leadership of Sudan’s former president Omar al-Bashir, for example, had at times accounted for up to 80 percent of the national budget, leaving little for education, healthcare and other vital government services.

Amidst the weak healthcare sector, misconceptions regarding blood donation especially among people from rural areas, suboptimal settings for donating blood, an inadequate infrastructure to store blood donations and a lack of raising awareness on the importance of blood donations by the former administration, had severe implications on the availability of blood transfusions.

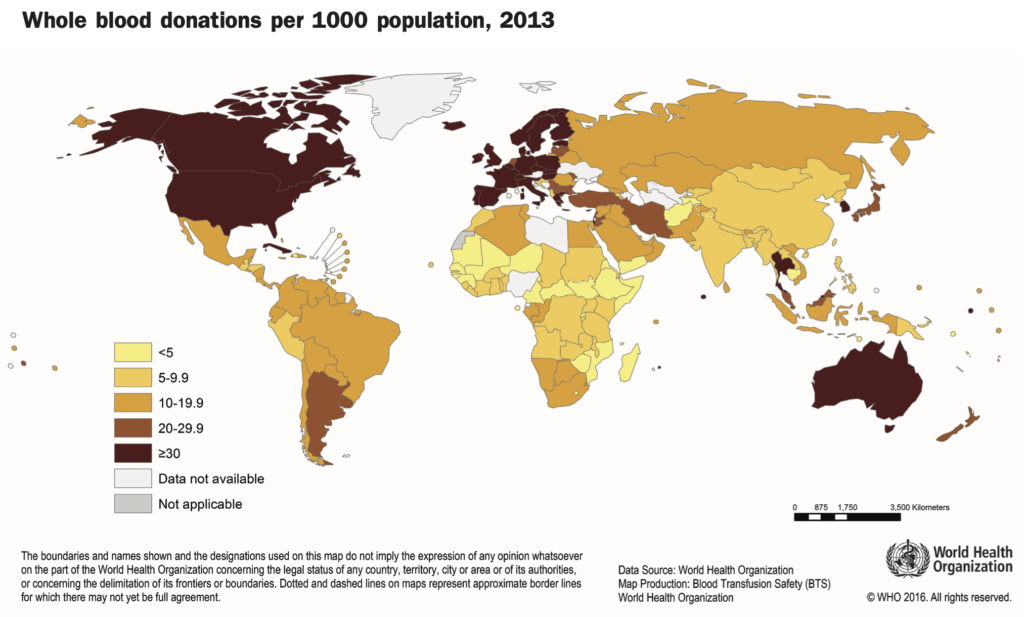

And blood transfusions are an essential pillar of modern medicine that save millions of lives every year. In Africa, 37 countries collect fewer than the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) goal of ten donations per 1,000 people. According to the latest data available, the WHO ‘Global Status Report on Blood Safety and Availability 2016’, Sudan collected approximately six donations per 1,000 people in 2013.

Although blood donors in Sudan’s capital Khartoum “consider blood donation an act of humanitarian goodwill, there is a lack of voluntary blood donors, and those that give blood, rarely do so repeatedly”, writes Ahmed Saad in a 2019 research paper. As a result, many patients in Sudan do not have access to a timely and safe supply. This became even more critical during the uprising against Sudan’s long-time ruler Omar al-Bashir and his government.

During the months of the revolution, protestors often faced violence, as a last resort of the former regime to quell the nationwide protests. According to a statement issued on July 18, 2019, by the Central Committee of Sudan Doctors (CCSD), 246 people were killed during the revolution, 127 of them on June 3, 2019, and 1,353 wounded. Blood transfusions were urgently needed for the injured and several civil society groups, like ‘SharAlhwadth’, ‘Sadagaat’ and the ‘Blood Bank Centre’, set out to raise the required blood donations.

In April 2019 Bashir’s regime fell, and in September a transitional government was formed. However, violent conflict flared up in some parts of the country, like in el-Geneina or Port Sudan. Blood transfusions yet again were needed to save the lives of injured people, and the country’s supply is still far from adequate.

“There is a lack of voluntary blood donors, and those that give blood, rarely do so repeatedly.”

Ahmed Saad

Following their successful work during the revolution, civil society groups collaboratively increased their efforts to raise awareness about the importance of donating blood and facilitate actual blood donations under the ‘Sudan’s Vein’ initiative. For AlAdwaa.Online, Alaa Eliass spoke with Ayaa Shamat, who works for the ‘Sudan’s Vein’ initiative:

Q: Ayaa, what is ‘Sudan’s Vein’?

A: ‘Sudan’s Vein’ is a blood donation initiative that spans across Sudan. It also aims to spread the blood donating culture in Sudan. ‘Sudan’s Vein’ doesn’t only save Sudanese people’s lives but it also unites them, as we get blood donations from all over Sudan to save people’s lives no matter from which ethnical group they are. All that counts – they are Sudanese.

Q: Who established ‘Sudan’s Vein’?

A: The initiative is a collaboration of volunteers from several initiatives (‘SharAlhwadth’, ‘Sadagaat’ and ‘Blood Bank Centre’). We all work together to accomplish the initiative’s goals.

‘Sudan’s Vein’ doesn’t only save Sudanese people’s lives but it also unites them.

Ayaa Shamat

Q: When and how was the ‘Sudan’s Vein’ initiative established?

A: The first blood donation initiative started on September 21, 2018, in the eastern Sudanese city Kassala. At the time, the treatment of patients with endemic diseases (Malaria, Chikungunya fever and Kala-Azar) depleted all reserves of the blood banks in Kassala. Amidst this situation, we certainly couldn’t get any blood donations from Kassala itself, so we urgently needed help from elsewhere.

So we started a campaign with the hashtag ‘#Kassala_vein‘ on social media. The campaign spread like fire, and people kept calling us asking how they can help, and where they can donate their blood. We established two centres to collect the blood donations within Khartoum, and in a short period, we had all the blood needed and sent it to Kassala.

The second campaign was after the tragedy of el-Geneina earlier this year. The number of victims required a large quantity of blood. Unfortunately, neither the blood banks in el-Geneina nor the central blood bank in Khartoum could cover the needs. We knew that we urgently needed to tell people about what was happening there and to collect the required blood donations. So I contacted our volunteers in el-Geneina and inquired about the needs.

Then we instantly started a social campaign with the hashtag ‘#Geneina_vein‘, calling upon people to come and donate blood from January 3 to 6. The campaign was very successful, and within a short time, we were able to collect the required amount of blood (about 230 blood transfusion units), and we sent it to el-Geneina.

“Within a short time, we were able to collect the required amount of blood.”

Ayaa Shamat

Shortly after, people violently clashed in Port Sudan, and many were injured. The blood banks in Port Sudan couldn’t cover the need. So again, we collected 150 blood transfusion units in Khartoum, and we sent it (Tarco Aviation transported the blood donation free of charge) to Port Sudan.

After that, we decided to call it ‘Sudan’s Vein’, collecting blood from all around Sudan and transferring it to whoever needs it within Sudan. We focus on people in need who live in small villages and suburbs as they suffer more than people in Khartoum.

Q: What are the obstacles facing ‘Sudan’s Vein’?

A: We are facing many, mostly financial challenges, but also safety challenges when working during a crisis, like in el-Geneina.

Besides, to ensure the safe transferring of blood, especially in the far-away states, we would need medical equipment like cold centrifuges that we use to separate blood plasma, or ‘Elisa’ (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) blood tests which we use to check for blood diseases in the donated blood.

And, donating blood saves lives, but unfortunately, people in Sudan have little awareness. We really need to spread this practice.

“Donating blood saves lives, but unfortunately, people in Sudan have little awareness.”

Ayaa Shamat