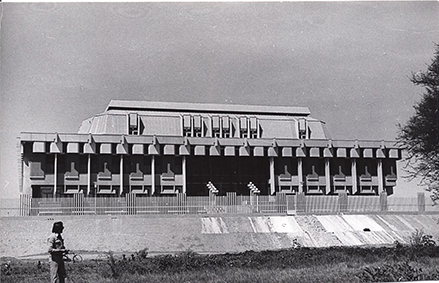

The Sudanese Parliament 1977. (cc) Caralaz

What is the future role of established political parties in Sudan, especially those accused of having worked with the ousted regime of Omar al-Bashir – will they play a role in the Sudanese political scene or will they be relegated to the dust bin of history?

Ghazi Salaheddine al-Atabani, head of the Reform Now Movement and National Front for Change (NFC), met with Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok, on January 31. According to al-Atabani, his meeting with Hamdok aimed at finding common ground for national rapprochement, to bring the country out of its current crises, especially the economic crisis.

“We must aim to achieve the country’s renaissance and prosperity, through diagnosing critical challenges facing the country, converging viewpoints and avoiding dependence on the views of political forces. This is an agreed-upon national political project,” said al-Atabani.

However, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC) and the Sudanese Professionals Association criticised this meeting along with any rapprochement with parties that were part of Bashir’s government that fell in April 2019.

“The meeting lacks political sensitivity and does not serve the advancement of the transitional period.”

Ismail al-Taj

Ismail al-Taj, a leading member of the Professionals Association, said that “the meeting of Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok with al-Atabani, in the office of the prime minister represents a great shock”. He stressed that “the meeting lacks political sensitivity and does not serve the advancement of the transitional period and the democratic transformation”. He then called on the cabinet to “provide quick and unambiguous clarifications about the alleged meeting”.

The exclusion of ‘Al-fakka’ parties

Al-Taj’s concern is rooted in the fact that several political parties collaborated with Bashir’s government. Therefore, some say, these parties are to equate with the by-then ruling National Congress Party (NCP), as they did not take a clear stance against the violent way protestors were dealt with.

Before the fall of Bashir’s regime, several parties formed a coalition under the name the Council of National Unity Parties. Their corresponding name on the Sudanese street is ‘Al-fakka’ parties – al-fakka, in Arabic, means the change one gets after making a purchase. This name is rooted in people’s low esteem of these parties.

Despite this view, it is worth noting that the Council of National Unity Parties did include some significant parties such as the (Original) Democratic Unionist Party (DUP – Original), led by Mohamed Osman al-Mirghani; the Federal Umma Party, led by Ahmad Babiker Nahar; the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP – General Secretariat), led by Jalal Youssef al-Digair; the Just Peace Forum, led by Mustafa al-Tayeb (the uncle of the ousted president Omar al-Bashir); the National Liberation and Justice Party (NLJP), led by Tijani al-Sissi; the Popular Congress Party (PCP), led by Ali al-Haj; and the Reform Now Movement, led by Ghazi Salaheddine al-Atabani.

In 2018, these parties, along with others, formed the National Front for Change (NFC), led by al-Atabani. Composed of 22 parties and armed movements, the NFC planned to run for the by-then planned 2020 elections.

“Political forces are trying to practice exclusion against others.”

National Front for Change

In April 2019, after the success of the revolution, the NFC tried to participate in the transitional government by holding a number of meetings with some stakeholders, including the Military Council at the time and the African Union. However, the FFC, which had high weight with the Sudanese people, rejected all their attempts. This, in turn, led the NFC to accuse the FFC of excluding them for the political process.

A statement issued by the NFC on April 20, 2019, after the meeting in Khartoum between al-Atabani and Moussa Faki, the African Union Commission (AUC) Chairperson, states that “political forces are trying to practice exclusion against others”. Since then, no attempts to include these parties in the transitional government have succeeded.

Subsequently, these same parties established the Coordination of National Forces (CNF). They announced their rejection of the agreement that was concluded between the Military Council and FFC, which was signed on August 17, 2019, in its entirety. They described it as being unjust, giving the FFC significant power during the transitional period and deliberately excluding the rest of the country’s political parties.

The tenacity of ‘Al-fakka’ parties

More than six months after the formation of the transitional government, the excluded parties haunted by their past haven’t given up just yet. Al-Atabani told the Al-Mijhar Newspaper that “being an integral part of the previous government certainly does not prevent me from practising politics”.

He added that “no one can prevent others from exercising their rights under any pretext. I do not regret anything I did, which I was convinced of. These issues should be differently assessed, and we will go our way, as we are used to, despite the difficulties.”

Nahar Osman Nahar, Secretary-General of the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) – Dabjo Wing, believes that being classified as part of the former regime is meaningless, “because we came to Khartoum and participated in the previous government through an internationally recognised agreement”.

“We will not be affected by what others say.”

Nahar Osman Nahar

Nahar acknowledged that these parties are being excluded and in an interview with the AlAdwaa.Online, he stated that “unfortunately, the exclusion is done in a very selective way as there are those who participated in the previous regime at a certain time and these are the ones now exercising this exclusion”.

“We are present in the political arena, and we are practising our work normally, and we will not be affected by what others say”, Nahar said.

Despite the confidence expressed by Nahar and al-Atabani, the future of their political involvement depends first and foremost on the confidence of the Sudanese people in their capacities to lead. Given their history of collaboration, the people’s trust will be hard, if not impossible, to earn.

The margins of relevance

Dr Moahmed Suleiman, a political and strategic analyst, put the question on the future of the “al-fakka” parties in a broader context which concerns the future of all Sudanese parties.

“The question should not be about the future of parties that had worked with the former regime, but about the future of political forces in Sudan in general,” said Suleiman, adding that “the reality is that the popular revolutionary tide was the one that toppled the regime and the role of parties was a marginal one”.

As for their current role, Suleiman said that “all political parties, in power or opposition, now have little impact, even those in the current transitional government”.

“All political parties, in power or opposition, now have little impact.”

Dr Moahmed Suleiman

Suleiman concluded that “political parties are not qualified to lead the [Sudanese] street. We are in a major political transformation phase, and this means that old forces, if unable to lead a renewal process, will need to leave the space to newly emerging political forces”.

Tariq Ismail, a 60-year-old Sudanese citizen, agrees with Suleiman. “This generation is now very conscious,” said Ismail, adding that “they [the people] will not fall for sectarian and ideological parties, whose historical conflicts led Sudan to its current state”.